written by, Michael Lee

Garage cinema is more a process and a sensibility than a body of finished films, although the result of the process when informed by the right sensibility is usually a video cassette containing what might loosely be called a film. The process privileges improvisation, haste, and delusion. The sensibility places all its hopes on the triumph of raw creativity over technical mastery, passion over polish. It is cinema in its purest form.

The first executors of garage cinema known to me were Bart Aikens and Scott Nollen, although I suspect garage cinema is as old as moving pictures themselves. Aikens and Nollen met in Iowa City, Iowa during the 1980s. Over the span of a few short years, they produced a series of ambitious, incompetent, outlandish films shot with next to no budgets, casts so small that actors had to double parts, and using the most primitive equipment at hand. Drawing upon their mutual passions for Bela Lugosi, Elvis, whiskey drinking, and sophomoric humor these two auteurs of garage cinema created a body of work that stands as a monument to their delusions and perhaps to the delusions of everyone.

As a form, cinema is always on the verge of collapse. Images juxtaposed Do not inherently tell a story. When the audience is deprived of such Basic grammatical codes as having one actor play one role, the problems of Cinema come to the fore. Nollen, a limited actor at best, often found himself covering multiple roles. His solution to this flagrant affront to continuity was to play one role as a cowboy. In their garage remake of the 1935 film The Raven, we inexplicably find Nollen sometimes drawling in a ten-gallon hat and other times trying to look dignified and "normal" (a difficult pose for any garage screen personality). At the climax of the film, Lugosi (played by Aikens, who has tackled the role of Lugosi numerous times in their collaborations) has Judge Thatcher (Nollen while not a cowboy) laying on a coffee table in Nollen's trailer house pretending to be threatened by a huge pendulum swinging over head. Ambition, delusion, poverty of means, and sublime indifference to the techniques of cinema merge in this magical moment, and the result is garage cinema.

Improvisation plays a tremendous role in creating the most sublime Moments in a garage film. For example in the Nollen-Aikens collaboration on The Frozen Bad, the two auteurs tell the story of Enoch Rector (played with fussy brilliance by Aikens). Surrounded by badness, Rector himself becomes bad. At a crucial point, Rector, now a fugitive from Justice, enters a road house. Naturally, Nollen's trailer house serves as both Rector's home and the road house. There he meets Nollen (not as a cowboy) who provides Rector with an unsatisfactory meal. Enraged by the renewed presence of "bad" In his life, Rector stabs Nollen repeatedly with a huge carving knife. As The blade repeatedly strikes his body, Nollen improvised the following Immortal line: "hey, cut it out, man." I have seen this film several times. That moment has never failed to elicit hoots of delight even from audiences unsympathetic to garage cinema.

Here is where we come to the philosophical superiority of garage cinema, with all its obvious limitations, to professional cinema. The cinema has become needlessly encumbered by the expensive accoutrements of filmmaking. The effect has been a massive, pan-cultural stultification. This lie of technique over creativity has diminished the sum of human creativity invested in the cinema, and that effect is unpardonable. A moment of mad and spontaneous dialogue can prompt far more pleasure than the stitched together visions of Hollywood accountants. For one thing, the process is pure in garage cinema. The idea of profit never enters into this anti-economy, for garage cinema bleeds money and never receives a transfusion. For decades, professionalized filmmaking has brainwashed people into thinking that cinema is expensive. It isn't. All garage filmmakers want or need is a VHS camcorder. Editing in the camera can be a drag, so some basic editing equipment isn't out of bounds any more than it's necessary. Taken as a source of pleasure, I honestly believe that garage cinema transcends conventional cinema. More importantly, garage cinema inspires activity, while conventional cinema fosters passivity. We can all be garage filmmakers. This availability to all celebrates life, It includes rather than excludes. It is, simply put, philosophically superior.

One of the most satisfying garage films I've participated in making was The Monsters and the Girl. Actors play multiple roles in this film as well, And the presence of a script results in line deliveries marred by halting And imperfect line memorization. Those problems, however, pale in comparison to the hopelessly daffy editing. For this film, Bart Aikens (then working independently from Scott Nollen) edited the film using two VCRs. Scenes are clipped short or run long, time codes and other prompts from the VCRs appear on the screen. The effect is sublimely beautiful, a vision of the pathos of being human laid bare. Films are better for flaunting their technical poverty. Stories can be told without sufficient means to make them look like a Hollywood film. This evident truth needs emphasis.

Garage cinema existed before the term. I drew upon the pleasures of Garage rock and roll bands and applied it to the art of cinema. Garage bands may have delusions of pending greatness. Sometimes they imagine themselves transcending their humble origins. They almost never do and are certainly better for it. The only essential difference between garage bands and bands we've heard of is corporate backing. The music industry has done a much better job of merging its professional project with the passions that motivate rank amateurs. The technical power of the lowliest garage band can rival and even surpass the technical mastery of many well-known bands. Cinema has failed miserably in this regard. Its elite has fostered illusions of technique mattering.

Garage cinema falls far shorter of the professional ideals of the art Form than garage rock and roll. Rather than striving to overcome its limitations, garage cinema celebrates them. More than corporate backing separates garage cinema from professional cinema. Garage cinema rises from a different sensibility all together. It flaunts its seeming incompetence. Wears its difference from professional cinema like a crown. Yet there's a fine line here that should not be crossed. Garage cinema cannot foreground incompetence by aping it. Garage cinema must not become self-consciously disorganized. Raw passion, not ironic poses fuel this magnificent art form. Garage cinema should be ambitious. The medium is sufficiently difficult th at limitations will inevitably reveal themselves on the screen provided that you follow some important procedural guidelines.

PROCEDURAL GUIDELINES FOR MAKING GARAGE CINEMA

1. Begin with a delusional and ambitious idea. Privilege in-jokes and obscure homages (my own contributions to garage cinema usually include some washing of socks). Require more actors than you have friends so that parts must be doubled. Envision locations more numerous and opulent than you can access. In short, place yourself at the free disposal of your vision without reckoning your technical limitations. Let your audience supply the details while you supply the general dream.

2. Work with friends or friends of friends. If you live near family (or better still with your family), you can draw on them as well. Try to persuade reluctant people in order to tap into their natural reticence. Gain assurances from totally unreliable people so that their unexpected bailing out on the project will throw up nearly insurmountable obstacles. Depend on these people over and over and never fail to be genuinely surprised by their latest shirking. Include gratuitous shots of family pets.

3. Make sure that your equipment is the most humble available. Make use of lame features of bad technology, like auto-focus features on camcorders. Shun tripods and lights unless they more get in the way than help. If you must work with film, strive to find super-eight cameras or formats so expensive that you'll never actually get the film developed. Potential films, or films that exist only in theory are a nice addition to any garage auteur's ouvre. Whatever format you choose, the limitations of your technology must be visible on the screen. Obviously a blank screen would count as a visible limitation. Try editing in the camera or using equipment not meant for editing to edit your work.

4. Disdain the entire idea of a budget. Treat the cast and crew (if that's anyone other than you) to items from the 59 cent menu at the nearest taco joint. Let lunch be your most expensive budget item. If you must spend money, make sure it's a sum inadequate to execute your ambitious vision. Certainly anything over $1000 is totally out of bounds.

5. Place improbable time limits on your project. Bart Aikens and I have made films in under four hours. Top that. If you take longer than a single weekend, you'd better be shooting a feature-length film, or better yet, a swollen film far longer than any conventional feature. Allow yourself to end the film hastily when the time limit nears. Make only the beginning or the middle or the end of a film. Bart Aikens and I have collaborated on a film with only a beginning called We Can't Have a Gang With Just Two People. In that film shot on location in Death Valley, suddenly I turn to the camera while playing two fourteen-year-old boys simultaneously occupying one middle-aged man's body and say "hi" in falsetto (an obscure homage to a childhood friend). Our camcorder battery suddenly went dead, and that was that. The film was over. Later, we collaborated on a film with only an ending called The Big Gundowns. The film opens with a complex plot about which the audience is largely left unaware coming to a rapid head. Blake Wilkins (a brilliant garage cinema actor) plays the evil Dr. Acrapone. Having killed the fourteen-year-old boys mentioned previously And Bela Lugosi (played by Aikens again), Acrapone shoots his girlfriend And accomplice repeatedly with his finger while saying "pow, pow, pow, pow, pow." He then picks up a valise filled with something (maybe insurance money), and walks out of Bart Aikens' condo complex wearing a dazed look on his face and tickling the walls. The camera suddenly whips to a clock radio, and we learn of his capture and pending execution through a newsbreak. It's a film with only an ending, no middle or beginning. The audience is charmed into enjoying their confusion while watching Acrapone suffocate Lugosi with a lobster (the most expensive item in the film's pitiful budget).

6. Reuse locations. The more pitifully obvious it is that the entire film was shot in your garage or dwelling, the better. If your dwelling IS a garage, that's better still. If you must shoot on location, allow the ambient noise to cover over dialogue. Under no circumstances should you gain permissions to shoot off your property. Bart Aikens is something of a master of just setting up and starting to shoot without saying a word to the proprietors of businesses or the owners of property. He has, to my knowledge, never received a shooting permit from any city. He has also never been fined or even scolded.

7. Allow for considerable improvisation. The idea of a shooting script, storyboard, or shooting schedule should be alien to garage cinema. If there is a script, actors shouldn't be given time to learn their lines properly. If there isn't a script, make things up as you go. Don't get much coverage of key scenes so that flubs have to stay in the finished product. Introduce fresh and superfluous characters so that whatever there is of a crew will have to appear before the camera unexpectedly. Dwayne Walker, host of this website, shot and edited Bart Aikens' superbly odd film Bart Aikens' William Soroyan's Timmy and Josh's Bear. In a crucial scene where the Main characters play cards in a mad house (a friend's back yard served as The mad house), Dwayne put on a silly dog mask and appeared before the Camera for a winning cameo. The dog mask was necessary because earlier in the Film Dwayne had already shown his face by stepping in for a no-show actor And taking a major speaking part. Wearing a dog mask is more drastic than doubling always as a cowboy, perhaps, but just as effective. Let projects ramble on out of control until your film is so long that no one will want to sit through it. I believe that Scott Nollen and Bart Aikens have made several sequels to Ed Woods' Plan 9 From Outer Space that are so long and so badly bulging with improvisation that not even Nollen and Aikens will watch them in their entirety.

8. Take yourself seriously, after all these are your filmed delusions. Talk about your creations in the same way you talk about Citizen Kane or Intolerance. Refer to your films in conversation as though people will Have heard about them. More importantly, network with other garage filmmakers. Drop other people's garage films into conversations. Write lofty scholarship about garage films. I recently had the privilege of debating Jack Valenti at the University of Oklahoma. I was part of a panel of faculty critical of Hollywood films. There was the law professor who attacked Hollywood for fostering a pornographic sort of violence. There was the daughter of blacklisted writers who felt that Hollywood betrayed her parents. There was the English professor who prefers European art cinema. Then there was me, I stood there and told Valenti and the crowd that Hollywood brainwashed people into thinking that there's a correct means Of telling stories, a means caked in technology that disenfranchises the Many while entitling the privileged few. In short, Hollywood pretends to be populist, but it is only populist at the consumption end. At the production end it is more elitist than grand opera or the ballet. If anything professional opera and ballet stimulates local participation by virtue of being so rare, so hard to access that lovers of the form willingly make do. Not so with cinema, which runs in every mall in America spouting the lie of technique over passion. I claimed that the best cinema was local, or even personal. I talked about Plan 13, the House of Elvis (a Nollen-Aikens collaboration) as though everyone in the room had seen this epic and proclaimed that it was by far a more important film than Tootsie citing all the philosophical justifications for garage cinema mentioned above. That's the campaign we all must fight and it begins with taking ourselves and Each other seriously (not too seriously, just seriously enough).

This list of procedures is not exhaustive nor does every one of them Have to be present for the film to constitute garage cinema. Think of it as a network of family resemblances. If enough of them are there, it's garage cinema. I've just listed some formulas that I've seen work. You may have your own nuances to bring to the process.

Finally, don't let any mention of finished films above convince you that garage cinema reveals itself mainly in finished products. The process Is key. It should be exhausting, frustrating, futile, and silly. In the end, few people will want to watch your garage films, so the act of making them needs to be valuable to you. Of course, you should try to make people watch your garage films over and over and over again. Bart Aikens has a gift for trotting out his creations at the slightest excuse. I've seen The Raven and The Frozen Bad innumerable times. Try to execute public screenings whenever possible. Enter your garage films in prestigious film festivals offering generous cash prizes, at least that way you'll know that some festival judges had to sit through the first few minutes of your latest opus. Screenings are fun, finished projects a source of pride, but Garage Cinema is a method leading to end products as diverse as human delusions. What these delusions share is an outlet driven by a sense of indignation That cinema has been left to the technocrats to define. Down with the professionals! Long live garage cinema!

Friday, April 02, 2010

Welcome to Garage Cinema

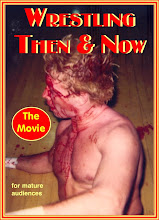

Garage Cinema is dedicated to grass roots movie making. We highlight movies made by regular people that are entertaining, ground breaking, and cover topics in ways that mainstream media never does! Plus, we live up to our name by reviewing vintage movies found in our garage that deserve a new audience.

'We', of course, is just a nice way of referring to 'me'.

Doesn't it sound more professional to refer to 'me' as 'we'? Maybe I should knock off that behavior since it sounds like I have multiple personality disorder!

'We', of course, is just a nice way of referring to 'me'.

Doesn't it sound more professional to refer to 'me' as 'we'? Maybe I should knock off that behavior since it sounds like I have multiple personality disorder!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)